Two weeks ago, I travelled back TO Tokyo from England where I had spent a very pleasant six months with family and friends whilst living in my home in Market Harborough, Leicestershire. One of the features of life in England that I have noticed on resuming permanent residence following many years of working and living overseas living is by how much society and local communities rely on volunteers both for services such as the community theatre and cinema, physical activities such as Park Run and the Ramblers, cultural activities such as music groups like choirs bands and choral groups, the Harborough Writers’ Hub of which I’m now a member, and of course the numerous charity shops which now dominate our High Streets.

In order to both contribute to as well as to get to know more about my new home town, last year I volunteered to help out at the Oxfam Bookshop which is well-stocked with second-hand (or ‘pre-loved’ as they’re now known) books, CDs, records and other items donated by members of the public for re-sale with proceeds going to support the work of Oxfam (a global organisation that fights inequality to end poverty and injustice). In fact today, 5 November, happens to be International Volunteer Managers Day when we recognise the work done by our Managers and Deputy Managers in the retail outlets.

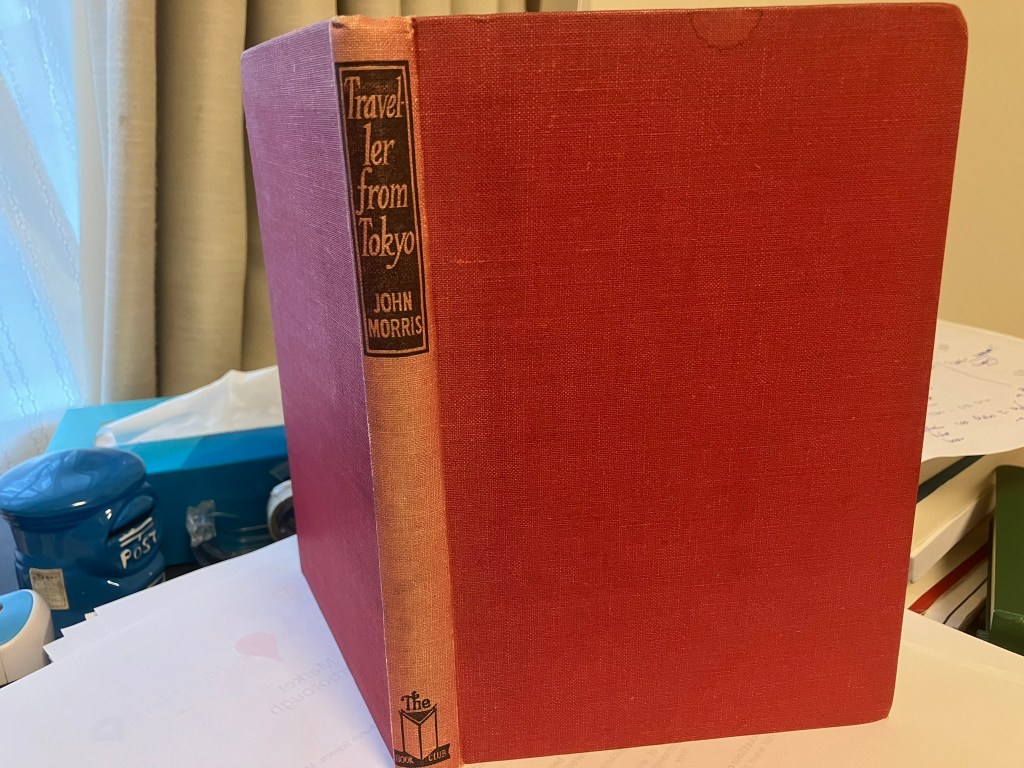

Obviously part-time staff such as myself do not receive any recompense for services but, in true English tradition, are entitled to tea and biscuits during our breaks! The shop’s kitchen has accumulated a supply of mugs over the years, and it was by coincidence and very appropriate that I should be allocated the following mug promoting an old penguin book a copy of which I have since tracked down and read although it wasn’t the Penguin edition.

And as one of my Oxfam colleagues commented, it seemed as if it were the book that I was meant to write. However, it wasn’t written by a 21st century retired member of the British Embassy in Tokyo, but by a gentleman appointed in 1938, by the Japanese Embassy in London to work as an adviser to the Japanese Foreign Office in Tokyo as well as doing some English language lecturing in Tokyo Universities. But, one of my final freelance pre-Covid jobs was teaching diplomatic English to the staff of the Japanese Foreign Office, so some cross-over.

Many of John Morris’ first experiences of Japan and its society in 1938 namely bureaucracy; attitudes and resistance towards learning and speaking English; rules and regulations; restaurants and food, were like mine when I first worked in Japan 41 years later in 1979. Given the timing of his stay with Japan’s dramatic entry into the Second World War his departure from Tokyo for England in 1941 was much earlier than he had expected and sadly he never returned. So, I feel a great affinity for John Morris; I am privileged to be able to come back regularly TO Tokyo to continue my own experiences, and to write about them, including the links I’m able to discover between my two homes despite the distance between them.

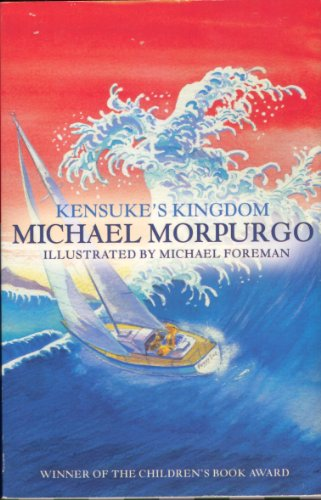

My last full weekend was no exception with another pleasant evening at the Market Harborough cinema to see Kensuke’s Kingdom an animated film based on a children’s book by Michael Murpogo which tells the story of a boy called Michael, who, whilst on a family sailing trip around the world was swept overboard in a storm and ends up on a small island in the Pacific which is inhabited by Kensuke, an elderly Japanese, himself a survivor of a Japanese battleship sunk during the Pacific War. Despite their age differences and linguistic challenges they become good friends until Michael is eventually rescued and they bid each other a fond, and tearful ‘sayonara’. In English but with Kensuke’s few words of Japanese voiced by well-known actor Ken Watanabe.

The following day, Japan was once again on the programme when I attended, for the first time, a concert given by the Market Harborough Orchestra, another community project, established in 2012 and now under the enthusiastic and talented baton of conductor Stephen Bell. The first piece they played was the Japanese Suite by British composer Gustav Holst who wrote it in 1915 at the request of a Japanese dancer, Michio Ito, who whistled some traditional Japanese tunes to Holst as he wrote the piece – and she must have been as good a whistler as she was a dancer as they are recognisable to those familiar with Japanese tunes.

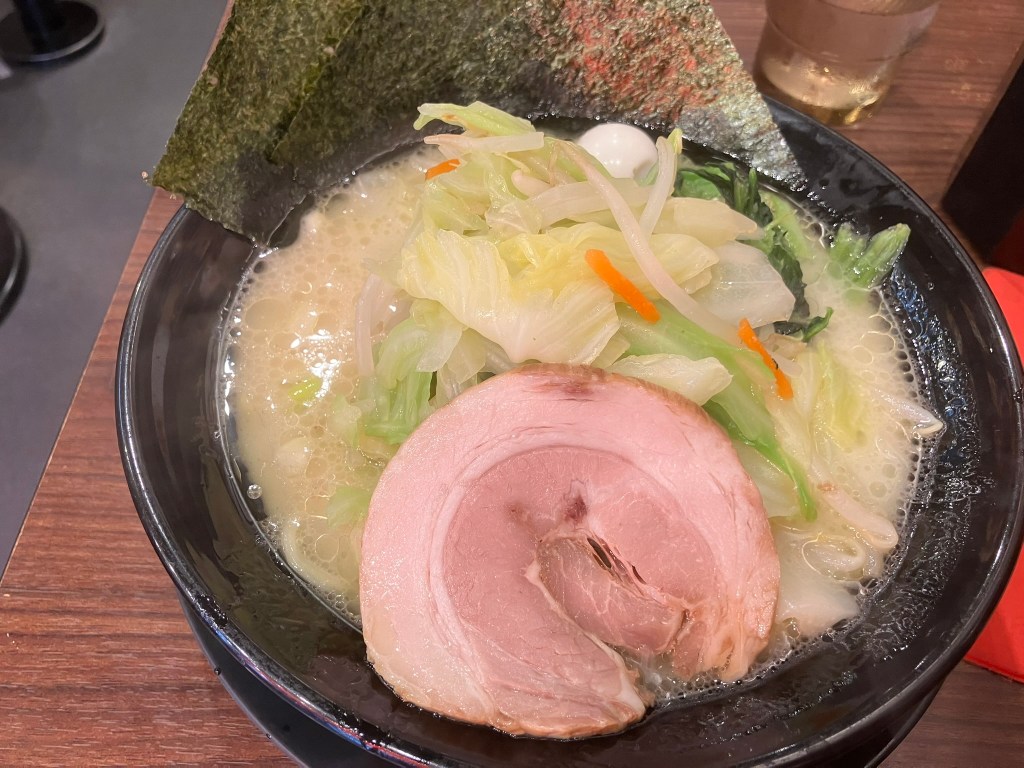

And so the time had arrived for me to bid a fond, and tearful sayonara to England’s Green and Pleasant Land to come back to the Land of the Rising Sun, marking departure FROM London via Paddington Station, and return TO Tokyo with traditional gastronomic delights which did not include, much to Paddington’s disappointment, any marmalade sandwiches.